- Home

- Margaret Merrilees

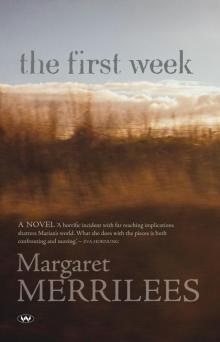

The First Week

The First Week Read online

Wakefield Press

Author photo by Anne Stropin

Margaret Merrilees was born and bred in Western Australia but now lives in Adelaide. Her idiosyncratic essays, which combine fiction, history and social commentary, have appeared in Meanjin, Island, Wet Ink and Griffith Review. Margaret is also author of the online serial ‘Adelaide Days’. The First Week won the SA Festival Award for an Unpublished Manuscript at Adelaide Writers’ Week in 2012. Her website is at www.margaretmerrilees.com.

Wakefield Press

1 The Parade West

Kent Town

South Australia 5067

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

First published 2013

This edition published 2013

Copyright © Margaret Merrilees 2013

All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from

any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research,

criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act,

no part may be reproduced without written permission.

Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Cover designed by Liz Nicholson, designBITE

Edited by Laura Andary

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author: Merrilees, Margaret, author.

Title: The first week: a novel / Margaret Merrilees.

ISBN: 978 1 74305 249 5 (ebook: epub).

Subjects: Australian fiction.

Dewey Number: A823.4

For our twenty-year-old selves.

monday

The day started like any other, though the cold was bitter. Jeb’s water bowl was rimmed with ice and frost crunched under Marian’s boot when she stepped off the verandah. She pushed her hands deeper into her pockets and curled her thumbs inside her fingers.

Ducking through the fence she wound her way along behind the machinery shed, dodging coils of rusty wire, until she could see the first tinge of yellow canola in the home paddock. Good. They’d sown earlier this year.

Sometimes from here the tops of the mountains were visible, a mirage, a slight interruption to the horizon. Today they were hidden but it was cold enough to imagine snow-covered peaks. The day for a snow trip.

It was a joke between the boys. A snow trip. A bitter joke from years back when Charlie told them at dinner about a school friend going skiing in New South Wales.

‘How come we can’t go?’

Mac went on chewing. ‘You wait long enough, Charlie, we’ll have snow here. I’ve seen it a couple of times. The year I left school there was enough on Bluff Knoll to make snowballs.’

Charlie stared at his plate in silence, radiating defiance.

Brian spoke for his little brother. ‘It’s not the same, Dad. In the Eastern States they have ski lifts and everything.’

Mac glared. ‘Do you know how much ski lifts cost? Eh? Never mind getting there.’

Brian muttered into his plate. ‘You stay in chalets right in the snow.’

‘Chalets!’ Mac slammed his knife and fork down. ‘Never mind bloody chalets. You get that wood chopped before it’s dark. I’m sick of telling you.’

Not long after that, he took the boys to the Stirlings for a day, his idea of a holiday. They came home scratched and wind-burned, and boasted about climbing Bluff Knoll.

Money was tight. It was background to their lives, day and night.

Now it was money for a tractor. Brian was right about the Ferguson. It was an antique, older than Marian herself. And with Mac gone it was Brian who had to wrestle with it.

Perhaps they could increase the second loan.

Marian turned along the firebreak at the edge of the south-east paddock, leaving the house far behind. Trees closed in along the boundary beside her. Down this side the fence was sagging badly. A couple of posts were almost gone and the wire broken. They’d have to get on to that soon.

Once, not long after Mac died, Marian found a kangaroo trapped in loose wire. There were raw patches in its fur where it had tried to get free, but by the time she arrived it was still, eyes wide with fear, one front leg dangling uselessly. There was nothing to be done but shoot it. She hated the way the body jumped with the impact. Nevertheless, she hefted the carcase into the ute and took it home for the dogs, just as Mac would have done.

She didn’t need Brian’s help to fix the fence, she thought now. It would be good to have a day out here at the edge of the bush. Jeb was too old to get this far on his own four legs, but he could come in the ute, a better companion than any human. Brian was as bad as Mac, grunting and swearing when the wire tangled or the strainer slipped. But with Jeb she could relax, knowing that he was dozing nearby.

Half a dozen roos lollopped slowly across the paddock ahead of her, paused, heads up, ears twitching, then bent to eat. As she got closer they swung away into the scrub in slow motion.

From here the ground sloped down to the creek where the mist was thickest. In another few minutes she was surrounded, only the fence visible. She walked more slowly, waiting for the cold whiteness to drift higher and disappear. The day would be clear and dry again. The melting frost and the mist were all that kept the plants alive.

By the time she reached the dam wall, she could see the blue of the sky and a pair of ducks beating upward into the last white trails.

Ahead was the low-lying scrub around the creek. Wet grass brushed against her legs as she pushed forward. Here the fence turned at right angles, making one corner of the farm. This had become her daily turning point, time to go back. But today she stopped, took her hands out of her pockets and blew on her fingers. The cold was making her thumbnail ache where the spanner had skidded. Without her glasses she couldn’t see the damage, but there was no escaping the dull throb. She slipped her thumb into her mouth. The old familiarity of the action was soothing.

Charlie used to suck his thumb before Mac and Brian stopped him. The little boy was caught between Mac’s forceful only sissies do that and Brian’s superior big-boy laugh. Marian hadn’t known how to help him. But they were right, of course. Charlie couldn’t go off to school sucking his thumb.

The top wire of the fence twanged when she pulled it. There was no reason not to go on, separate the strands, clamber through. She’d done it a hundred times and sat near the creek waiting for birds, watching the emu families grow up, chicks following dad on longer and longer expeditions.

But it was different now. There was a claim on it. This fence, a fence she’d ignored for years, had taken on new meaning. Where she stood was her land. The other side was theirs. Someone’s. Those Noongars from town.

What would they do with it? Any more clearing would be a disaster. The salt was already bad down here.

Marian looked back up the slope and thought, as she did every day, about water, the key, central to everything they did. Without it the soil was nothing. But with the water came the salt. The rain soaked in and seeped out again bringing salt to the surface and acid too in these low-lying areas. Under her, under the soil, there were layers, many layers, curved cradles of rock. The curves held the secret water, the aquifer, water flowing around and over itself, groundwater that ran for miles, collecting finally in the Pallinup.

She imagined it as dark silent pools, suspended underground.

You wouldn’t guess, just standing on the surface.

Brian had sown lucerne and it was up—a green carpet spread across the paddock, patchy in parts, but not too bad. It was supposed to be deep rooted enough to hold the water down. That was the plan. Two years of lucerne to one of cropping.

But the scrubland was past even that. An old stock trough lay rusting against the fence. In Mac’s father’s time there was fresh water here. Sheep

drank where now the ground was spoilt by tell-tale tidemarks of white.

Saltbush might grow, though it was a strange idea. Saltbush was something that belonged much further out, in the marginal country to the east. But people were breeding sheep that did well on salt. They could try.

How would you keep up with all this if you didn’t watch it every day? Those people from town wouldn’t have a clue.

It was the last thing she and Brian needed—new neighbours upsetting all they’d done.

Marian turned her back and started for home.

The chooks were grumbling. She let them out of the shed and checked the boxes. No eggs. The latest chickens were adolescent and leggy, too young to lay. And the old lady wasn’t laying, nor was the Australorp. The Australorp was a present from Michelle, and Marian didn’t trust it. All show.

On the way back she was distracted by the veggie garden. The peas needed tying and the birds had pulled the mulch away from the lettuce seedlings. The caulis were big and strong though, and the silver beet would survive anything.

When she stood up she could see Michelle’s car across the paddock near the front gate, heading for the other house. She’d be coming home from waiting with Todd for the school bus. You couldn’t just leave them beside the road when they were little. There’s time for him to be tough later on, Marian said to an invisible Mac.

Once the kettle was boiled she made tea and toast and took it out on to the verandah, ignoring the pips for the nine o’clock radio news. So it wasn’t until much later that she saw the light on the answering machine flashing.

Hi. Mrs Anditon? A girl’s voice. My name’s Sam. I’m a friend of Charlie’s. Um … there’s a problem. Charlie might be in trouble. The sound was suddenly muffled, as though someone had put a hand over the receiver, then it cleared again. I’ll ring you back I guess.

The click of the phone being hung up.

Marian’s heart sped. Trouble. What sort of trouble? An accident? But you wouldn’t say might be if it was an accident. Would you?

She played the message again. The girl sounded nervous and hadn’t left a number.

Marian made herself breathe more slowly. If it was anything serious, she would have heard.

Brian had told her there was some way of ringing a number back. But she couldn’t remember, hadn’t really been listening.

While she stood there, the phone rang again. Marian grabbed at it, breathless, and tried to make sense of the voice at the other end.

As if from far away she heard someone, herself, saying the right things. Yes. Good. I’ll be here. And then carefully hanging up.

Good.

Whatever it was, it certainly wasn’t good.

Marian’s knees trembled and she clung to the edge of the kitchen bench.

The girl would ring back. She remembered that bit. As soon as we know for sure.

Marian walked out onto the verandah, not knowing where she was going, and stood blindly on the path.

Not Charlie.

Brian was the one who did things. Action man, Charlie called him, admiring size and strength. Though when they were older it didn’t sound so much like admiration.

They were different. Brian grumbled about chores but got on with them. Charlie came up with endless wild ideas and excuses. And even when it was a treat. Like that time Evie visited and announced she’d take the boys back to the city so they could go to the zoo. Brian went straight to his room, put his pyjamas in a bag and came back to say he was ready. But they couldn’t find Charlie anywhere. Finally Marian tracked him down under the tank stand.

‘Why are you hiding?’

Perhaps he was scared at the idea of being away from home? But when he came out into the light his eyes were bright and he was smiling.

Taking his arm she pulled him upright, exasperated. ‘Do you want to go or not?’

He nodded vigorously. But even when she finally waved them off in Evie’s car he didn’t speak, just sat in the back hugging his pleasure to himself.

Could the girl on the phone have meant Brian?

No. That was ridiculous. Brian was here somewhere, not in the city. What was he doing? Yesterday afternoon when they were checking the ewes he’d said something about today …

She’d have to tell him about Charlie … whatever it was.

Trouble.

Nothing in the garden had changed since the early morning, but now she saw it without comprehension. The straggly wattles, the clothesline, the scuffed dirt near Jeb’s kennel, all the comfortable familiarity had vanished.

She stared at the nearest plants, forcing herself to focus.

Hydrangeas.

The leaves were drooping, done for. Useless fussy things they were. They didn’t like the frost and they didn’t like the heat. They guzzled water all summer. One day without attention, and they wilted. In defiance of Mac’s scorn of flower beds Marian had kept them going, and also out of loyalty to some old idea of elegance—a table covered with a lacy cloth, cups in saucers, scones on a dish. In the centre, a perfect hemisphere of pink and mauve petals in a cut glass vase. An afternoon tea party table. Somewhere else. Somewhere where there was more time and more water.

This morning, anxiety tight in her gut, Marian didn’t want hydrangeas. She bent down and yanked at the spindly remains. One plant came up, but the other was deeply rooted. It was only when she squatted to get a firmer grip that it came free in a splatter of soil.

Straightening her back, she carried the plants down to the compost heap against the paddock fence and pushed them into the back of the pile. On the way back she saw that she’d dropped one stem on the path. She nudged it with her foot then let it lie.

But she shouldn’t be wasting time out here. What if the phone rang and she didn’t hear?

The empty house stood in front of her, and in the house, threatening everything she knew, was the phone.

Who was this girl, anyhow?

It must be a mistake. That’s what it was. There’d be some explanation. No, no. That’s not what I meant …

For a moment she felt every muscle in her body primed for the sound, but the phone was silent, and she sagged again.

How did Brian feel about flowers? Funny that she didn’t know, had never asked him. Michelle usually had something by the back door. A pot of petunias, pansies in winter.

All those years Brian had argued with his father as though he hated him. But now that Mac was dead, Brian wouldn’t hear a word against him. Sometimes Marian started to call her son Mac, and had to pull herself up.

Perhaps it was useful, that fighting. It got things out into the open. Better the anger you could see than Charlie’s brooding smile.

Charlie.

She forced her legs to carry her to the edge of the verandah, then turned away again, drifting.

She probably should have made Charlie talk more.

Made him.

All the things his father tried to make him do. Tried and failed.

Not this, though. It’s a mistake.

The girl would ring back in a minute and explain everything. Or, better still, Charlie would ring, laughing about the mix-up.

If only Mac hadn’t died … but she stopped herself. That thought was a dead-end and she had learned to push it away.

But still, a boy needed a father.

Explosions between Mac and Brian had been common, but not between Mac and Charlie. When they did happen they were worse. Charlie was quick-thinking, circling round his father, taunting. Mac was bigger, an adult, but slow. At first he’d be baffled by Charlie, but then it would turn into fury.

He’s only a boy, Marian said to the empty yard, a bright boy. He sees beyond the farm. You can’t punish him for that.

Jeb nuzzled at her leg, wagging his whole stiff hindquarters, cloudy eyes beseeching. She bent down and scratched behind his ears.

But Charlie wasn’t a boy, not any more. That was the thing.

The back of her mouth felt strange, as though bending over might m

ake her vomit, or faint.

She must check the guns. Brian had the semi-automatic. Surely to God he kept it locked up. Then there was the old twenty-two. It was a year or more since she’d last seen that.

When she came here, after she and Mac were married, she hated the guns, the sudden shattering of the quiet. But Mac made her learn to shoot, said she had to know how to look after herself, stuck out on a farm. What if he was away? He was tense and impatient, she couldn’t ask him anything. That wasn’t his way of teaching. It was business, nothing relaxed about it. Guns are not toys. His whole body would be strung tight until the gun was cleaned and put away again. At first she thought it was her, her reluctance and clumsiness. But later she watched him do the same thing with the boys. It’s the army, she wanted to tell them. He doesn’t like guns. It’s not you he’s angry with. But it would have been wrong to talk about Mac behind his back.

Gradually Marian realised the need for guns, saw what a fox could do, or an eagle … half-eaten chooks, lambs with their eyes pecked out, a ewe, still alive, with its udder chewed. And then there were the snakes. She made herself practice, endless beer cans on a fence post.

In her second year at the farm there was a spate of deformed lambs. Mac found her nursing one, a big male, alive and perfectly formed except for the bones of its skull. Its brain was hanging out the back of its head in a soft sac. The mother was nuzzling worriedly and Marian, pregnant herself, was horrified. Mac took the lamb in his arms and went behind the shed to shoot it.

‘I’m sorry, Marian,’ he said when he came back, and he was gentle with the distressed ewe. But Marian had gone numb.

She found herself now at the woodheap and swung the axe. The block of wood split sweetly, but the violence of the impact shocked her, and the sound of the blow.

Too loud.

The feeling was an old one. Don’t draw attention to yourself. A childhood hide-and-seek feeling. If you were hidden, then you couldn’t tell how close the finder was and you had to keep very still. It was the waiting she hated, knowing that something would soon be expected of her, that she would have to leave the safety of her hidey hole, make a break.

The First Week

The First Week